Introduction

Why async/await looks the same in both languages, but hides radically different philosophies

In recent years async/await has become ubiquitous: we use it in Python with asyncio, we find it in JavaScript, we see it appearing in HTTP frameworks, database clients, and API wrappers. However, when switching to Rust and Tokio, many developers get a strange feeling: the syntax seems familiar, but the way you need to think about asynchronous code is radically different.

In this article I’ll try to bring order to the chaos: we’ll start from the problem that async actually solves, then compare Python’s model with Rust’s, using Tokio as a lens to understand what it means to have a “zero-cost” but compiler-driven runtime. We’ll conclude with some practical guidelines — and a few stories from the field drawn from recent PRs on Tokio and Python projects.

This wasn’t just a theoretical exploration. As you’ll see later, I had the opportunity to contribute to both Tokio and Python projects in the GenAI ecosystem, an experience that deepened my understanding of the differences between these two async models.

The Problem That Async Actually Solves

Before diving into details, it’s worth resetting our vocabulary: concurrency and parallelism are not synonyms, and async is not a magic wand to “go faster”.

I/O-bound vs CPU-bound

The fundamental distinction is between:

- I/O-bound: the program spends most of its time waiting for something external — an HTTP response, a database query, a file from disk, a token from an LLM.

- CPU-bound: the program spends most of its time computing — compressing data, training a model, hashing passwords.

Async shines in the first case: instead of blocking a thread (expensive in memory and context switches) while waiting, we yield control to an event loop that can advance other tasks in the meantime.

The OS Thread Model and Its Limits

The classic “one thread per request” model works well up to a point. A server handling 10,000 simultaneous connections with as many threads risks:

- Consuming gigabytes of memory (each thread has its own stack).

- Spending more time context switching than executing useful code.

- Becoming unpredictable under load.

The event loop solves the problem by multiplexing many I/O operations on a few threads (often just one). But it requires a mental shift: each task must explicitly yield control at points where it waits for something.

An Example Identical on the Surface

Let’s look at two snippets that do the same thing: fetch a user from the database and their profile from an HTTP service, then merge them.

|

|

|

|

The syntax is almost identical. The question that will guide the rest of this article is: why do these two snippets live in such different worlds?

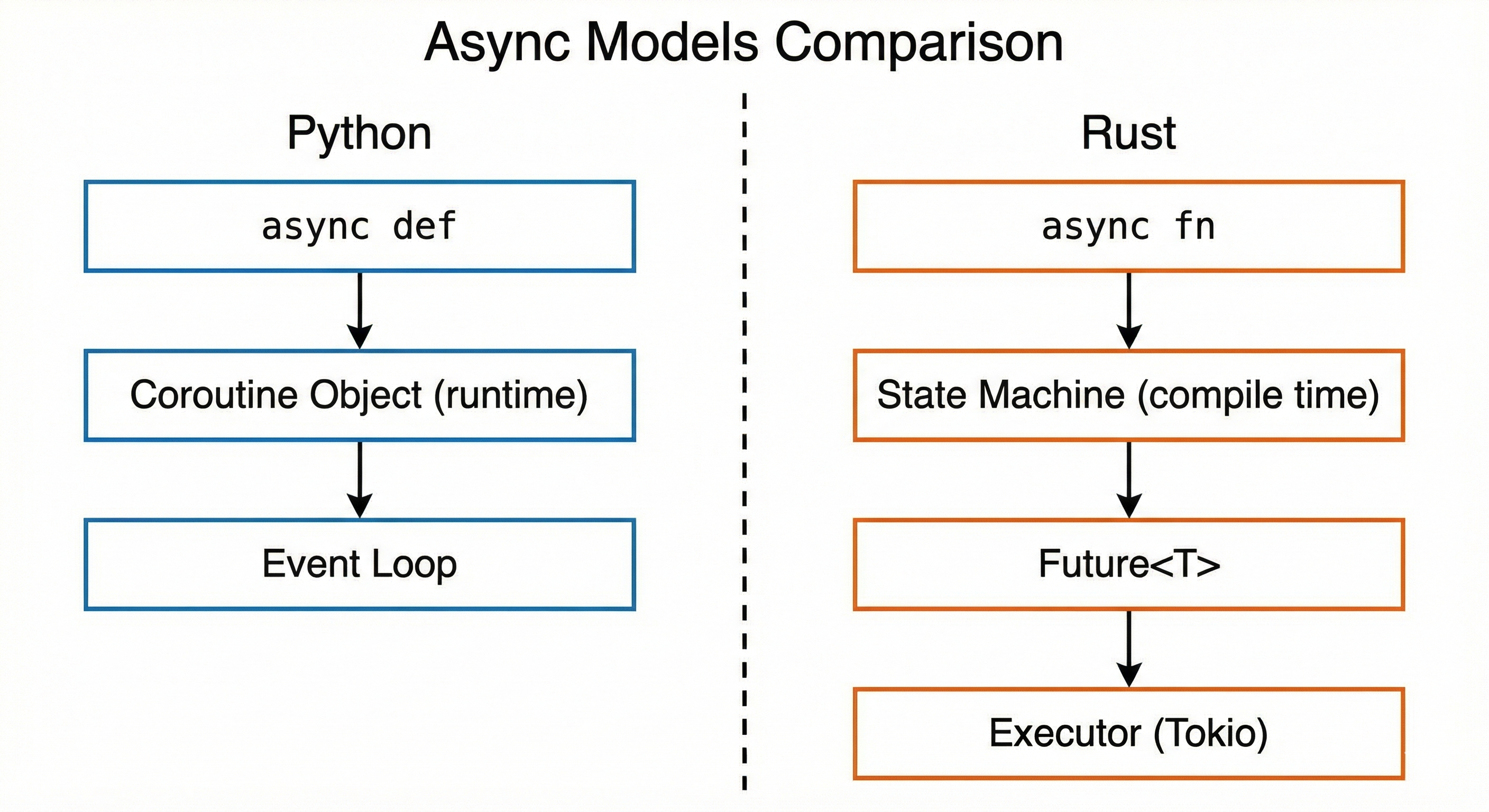

Comparison between async models: Python with generous runtime vs Rust with compile-time state machines

Comparison between async models: Python with generous runtime vs Rust with compile-time state machines

Python: Async as a Runtime Feature

In Python, async/await is a high-level pattern attached to a generous runtime that “takes care” of many details. This makes it extremely productive, but hides costs that eventually emerge.

How the Event Loop Works

When you write async def, Python creates a coroutine object. When you call await, the coroutine yields control to the event loop, which can advance other waiting tasks. The event loop is typically single-threaded and provides:

- A scheduler for coroutines.

- I/O primitives (sockets, subprocesses, files with limited support).

- Integration with external libraries (aiohttp, asyncpg, aioredis, etc.).

The model is simple and powerful, but has some characteristics to keep in mind:

- Coarse granularity: context switches happen only at

awaitpoints. If you do heavy work between oneawaitand another, you block everything. - Dynamic types: coroutines are opaque objects; the type system doesn’t tell you much about what they contain or how much they cost.

- Memory overhead: each task has a relatively high (hundreds of bytes) and non-transparent overhead.

The GIL: The Elephant in the Room

Python has the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), which prevents parallel execution of Python bytecode in the same process. For I/O-bound code this often isn’t a problem: while waiting for the network, the GIL is released.

But beware: if inside an async def you do pure CPU-intensive work (heavy parsing, numerical calculations in pure Python, etc.), you’ll block the entire event loop. The classic solution is to offload to a thread pool or process pool — but this introduces complexity and overhead.

A Common Mistake: Async That Isn’t Async

This point is particularly insidious. I recently contributed to datapizza-ai, a Python framework for GenAI solutions, where I found a very common but problematic pattern:

|

|

The a_embed() method was marked async, but contained no await. Result: anyone calling it with await a_embed(...) expected to yield control to the event loop, but in reality the code blocked everything for the entire duration of the embedding.

The fix was to use asyncio.to_thread() to offload the blocking work:

|

|

This pattern is much more common than you might think. The takeaway: async def doesn’t magically make code non-blocking. If there are no awaits on real I/O operations, you’re just adding overhead without benefits.

When asyncio Shines

Despite its limitations, asyncio is excellent for:

- API servers that mainly do I/O (FastAPI, aiohttp).

- Orchestration of calls to external services.

- Advanced scripting where development speed matters more than pure performance.

- Prototyping systems that might evolve toward more performant solutions.

The ecosystem is huge, the learning curve is gentle for those already using Python, and for most use cases it’s good enough.

Rust: Async as a State Machine

In Rust, async/await has the same syntactic appearance, but materializes into something completely different: a state machine generated by the compiler, with memory layout known at compile time.

Futures: Not Magic, But Types

When you write async fn in Rust, the compiler doesn’t create a dynamic “coroutine object”. Instead, it generates a type that implements the Future<Output = T> trait. This type is an explicit state machine:

- Each

awaitbecomes a suspension point. - The function’s state (local variables, execution point) gets “packed” into the generated struct.

- The Future’s size is known at compile time.

This means that:

- No hidden allocations: you know exactly how much memory each task uses.

- No runtime overhead for coroutine management: the compiler has already done all the work.

- Complete type safety: the type system tells you if a Future is

Send(can cross threads) orSync(can be shared).

The Runtime Is External: Enter Tokio

But Futures alone don’t do anything. They need an executor to run them and a reactor to handle I/O. This is where Tokio comes in, the most widely used async runtime in Rust.

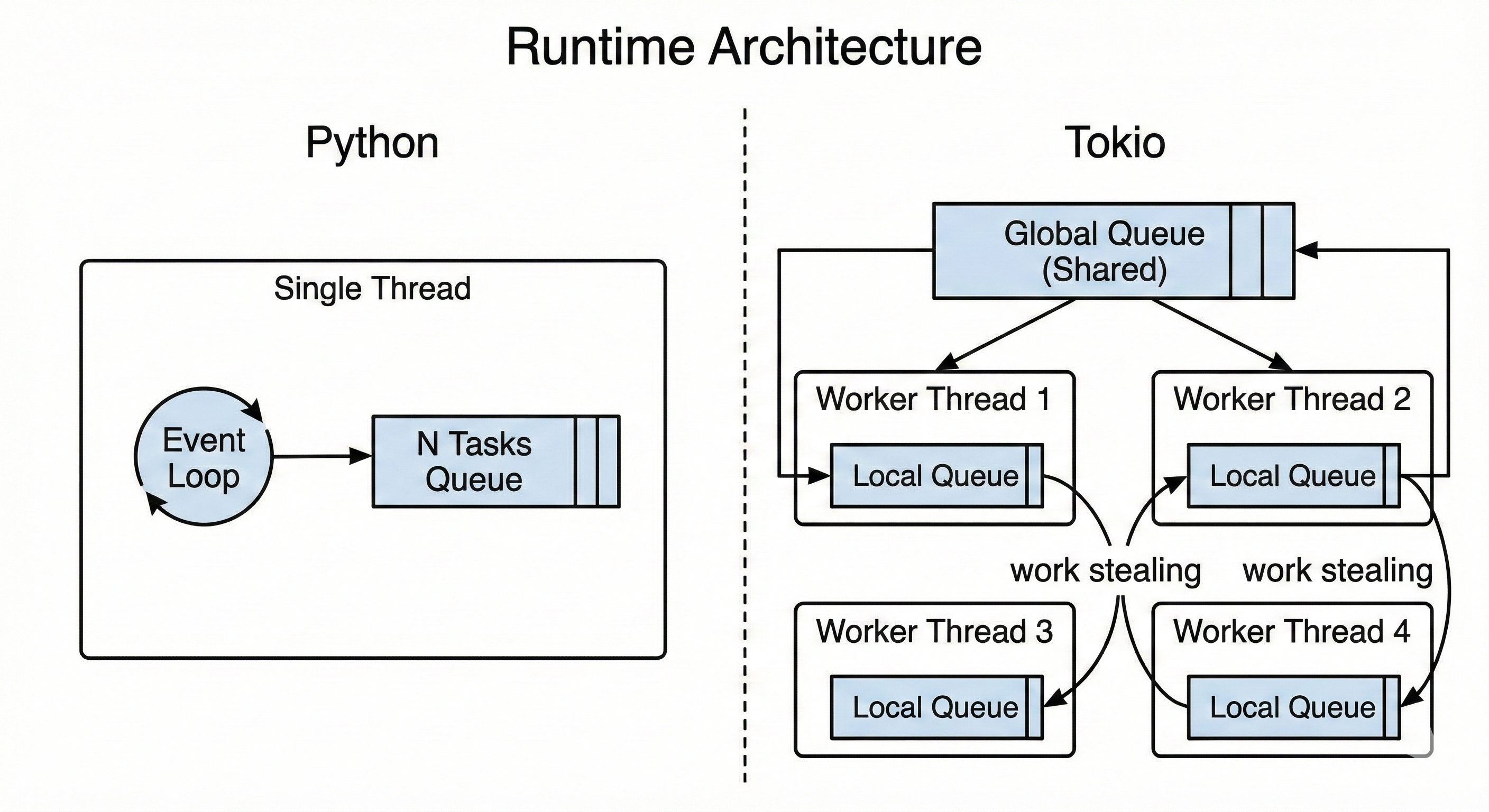

Tokio provides:

- A thread pool with work stealing (idle threads “steal” tasks from busy ones).

- A scheduler for Futures.

- An I/O reactor based on epoll/kqueue/io_uring.

- Primitives like

TcpStream,UdpSocket, timers, MPSC channels, async mutexes.

The #[tokio::main] macro creates the runtime and executes your async fn main:

|

|

A crucial point: in Rust you can choose different runtimes. Tokio is the most popular, but alternatives exist like async-std, smol, glommio (optimized for io_uring). The contract between your code and the runtime is the Future trait, which makes the ecosystem very composable.

The Cost of Precision: Send, Sync, Pin

Rust’s precision comes with an initial complexity cost. Three concepts that don’t exist in Python (or are implicit) become explicit:

- Send: “This value can be moved to another thread.” If your Future contains an

Rc<T>(non-thread-safe reference counting), it won’t beSendand you can’t use it withtokio::spawn. - Sync: “This value can be shared between threads.” Relevant for shared data in async contexts.

- Pin: “This value cannot be moved in memory.” Necessary for some Futures that contain self-references.

At first these constraints seem hostile. Over time, they become a safety net: the compiler prevents you from writing data races, even in complex async code.

Tokio vs asyncio: Direct Comparison

Let’s compare the two approaches on concrete dimensions.

Runtime architecture: asyncio single-threaded with event loop vs Tokio multi-threaded with work stealing

Runtime architecture: asyncio single-threaded with event loop vs Tokio multi-threaded with work stealing

| Aspect | Python asyncio | Rust + Tokio |

|---|---|---|

| Type model | Dynamic coroutine | Future<T> with layout known at compile time |

| Runtime | Integrated in stdlib | External library, pluggable |

| Scheduling | Cooperative, single-thread by default | Cooperative, multi-thread with work stealing |

| GIL | Yes, limits CPU parallelism | No, full parallelism |

| Memory control | Limited, hidden allocations | Explicit, zero-cost abstractions |

| Type safety | Dynamic | Static, Send/Sync/Pin |

| Learning curve | Gentle | Steep, then consistent |

| Ecosystem | Huge, mature | Large, growing |

Predictability vs Development Speed

Tokio and Rust force you to think ahead about:

- Lifetimes of data shared between tasks.

- Which Futures are

Sendand which aren’t. - How to handle pinning for advanced APIs.

This extends initial development time. But the payoff is:

- Fewer surprises in production: if it compiles, you probably don’t have data races.

- Predictable performance: you know how much memory each task uses, there’s no garbage collector.

- Ability to squeeze the hardware: real multi-core, tail latency under control.

My Contributions: Field Experience

While exploring these two async worlds, I had the opportunity to contribute to projects in both ecosystems. These hands-on experiences solidified my understanding of the philosophical differences between Python and Rust.

Tokio: Time Module Documentation

I contributed to Tokio with two PRs focused on the time module documentation:

PR #7858 — Improving documentation on time manipulation in tests. The problem: many users discovered through trial-and-error subtle behaviors like the fact that spawn_blocking prevents auto-advance of time when paused, or the differences between sleep and advance for forcing timeouts in tests.

In Python, these nuances often don’t exist — or are hidden behind abstractions that “just work” until they don’t. In Tokio, the runtime exposes these details because they’re part of your mental model. The documentation now clearly explains when to use which approach:

|

|

PR #7798 — Cross-reference in the documentation of copy and copy_buf, with focus on SyncIoBridge. In Rust there are two I/O “worlds” — synchronous (std::io) and asynchronous (tokio::io). Many existing libraries (hashers, compressors, parsers) are synchronous. SyncIoBridge is the adapter that allows using them in async context without blocking the runtime.

The very existence of this bridge highlights a fundamental difference: in Rust you must be aware of the sync/async boundary, while in Python this boundary is much more blurred (and often a source of subtle bugs).

datapizza-ai: Async That Wasn’t Async

On the Python front, I contributed to datapizza-ai, a framework for GenAI solutions. I found a very common but problematic pattern: methods marked async that contained no await.

|

|

Anyone calling await a_embed(...) expected to yield control to the event loop, but in reality the code blocked everything for the entire duration of the embedding. The fix was to use asyncio.to_thread():

|

|

Reflections from Experience

Contributing to both ecosystems crystallized a key difference:

- In Rust/Tokio, the compiler forces you to think about async/sync boundaries. You can’t “pretend” something is asynchronous — the type system exposes you.

- In Python/asyncio, the language’s flexibility allows patterns that seem correct but hide problems. The

async defwithoutawaitbug is common precisely because Python doesn’t stop you.

The review experience on Tokio was particularly instructive: the community is as attentive to documentation as to code, because in an explicit runtime like Tokio, understanding the mental model is as important as using the API.

When Python, When Rust: Practical Guidelines

After all this theory, the practical question: what do I use for my next project?

Stick with Python/asyncio if:

- Most of the work is high-level I/O-bound: HTTP calls, microservice orchestration, database queries, LLM interaction.

- The bottleneck is outside your process: response time of external APIs, network latency, database slowness.

- You need the Python ecosystem: pandas, numpy, ML libraries, data engineering tooling.

- Development speed matters more than pure performance.

- You’re prototyping something that might evolve.

The key message: if your main problem is domain complexity and not system complexity, asyncio lets you move fast with a good enough cost model.

Consider Rust + Tokio if:

- You have stringent requirements on tail latency (p95, p99) or throughput under load.

- You’re building infrastructure: high-load central services, data platform components, gateways, proxies.

- You can’t afford memory leaks or unpredictable behavior under stress.

- The execution model isn’t an implementation detail, but your actual product.

- You want real multi-core without fighting with the GIL or multiprocessing.

The key message: Rust + Tokio become interesting when how the code executes is as important as what it does.

Conclusion: Same Keyword, Different Philosophies

async/await has become a buzzword, but beneath the surface it hides very different models.

In Python, async is a promise of simplicity: “think about the logical flow, the runtime takes care of it”. It’s a high-level programming pattern, optimized for productivity and iteration speed. The cost is a certain opacity: you don’t always know how much a task costs, you don’t always know if you’re actually yielding control to the event loop.

In Rust, async is a promise of control: “think about the layout of your code in time and space, the compiler helps you not make mistakes”. It’s a zero-cost abstraction that materializes into state machines with memory known at compile time. The cost is a steeper learning curve and a type system that sometimes seems hostile.

Neither approach is “better” in absolute terms. They’re optimized for different problems, different teams, different project phases. The important thing is to understand which trade-off you’re making when you choose one or the other.

And if after this article you want to explore Tokio more deeply, in the next post we’ll dive into the runtime details: how the scheduler works, how Futures are implemented, and what really happens when you call .await.

Future Horizons: Where Async Is Heading

The async ecosystem in both languages is evolving rapidly:

Python: PEP 703 (optional GIL removal) and work on “free-threaded Python” in 3.13+ could radically change the landscape. If the GIL becomes optional, asyncio might no longer be the only path to performant I/O-bound concurrency. However, the async/await model will remain relevant for its ergonomics.

Rust: The ecosystem is consolidating around Tokio, but alternatives like async-std and smol offer different trade-offs. Support for async fn in traits (stabilized in Rust 1.75) opens new possibilities for generic APIs. Work on io_uring (via tokio-uring and glommio) promises even better I/O performance on Linux.

Interoperability: Projects like PyO3 allow writing Python extensions in Rust, combining Python’s productivity with Rust’s performance. For critical async workloads, it’s possible to implement the “hot path” in Rust and orchestrate from Python.

The future isn’t “Python vs Rust” but rather understanding which tool for which problem. The same async/await keyword will continue to mean different things in both worlds — and that’s a feature, not a bug.

PRs cited in this article: tokio#7798 (SyncIoBridge docs), tokio#7858 (time manipulation docs), datapizza-ai#106 (async embed fix).